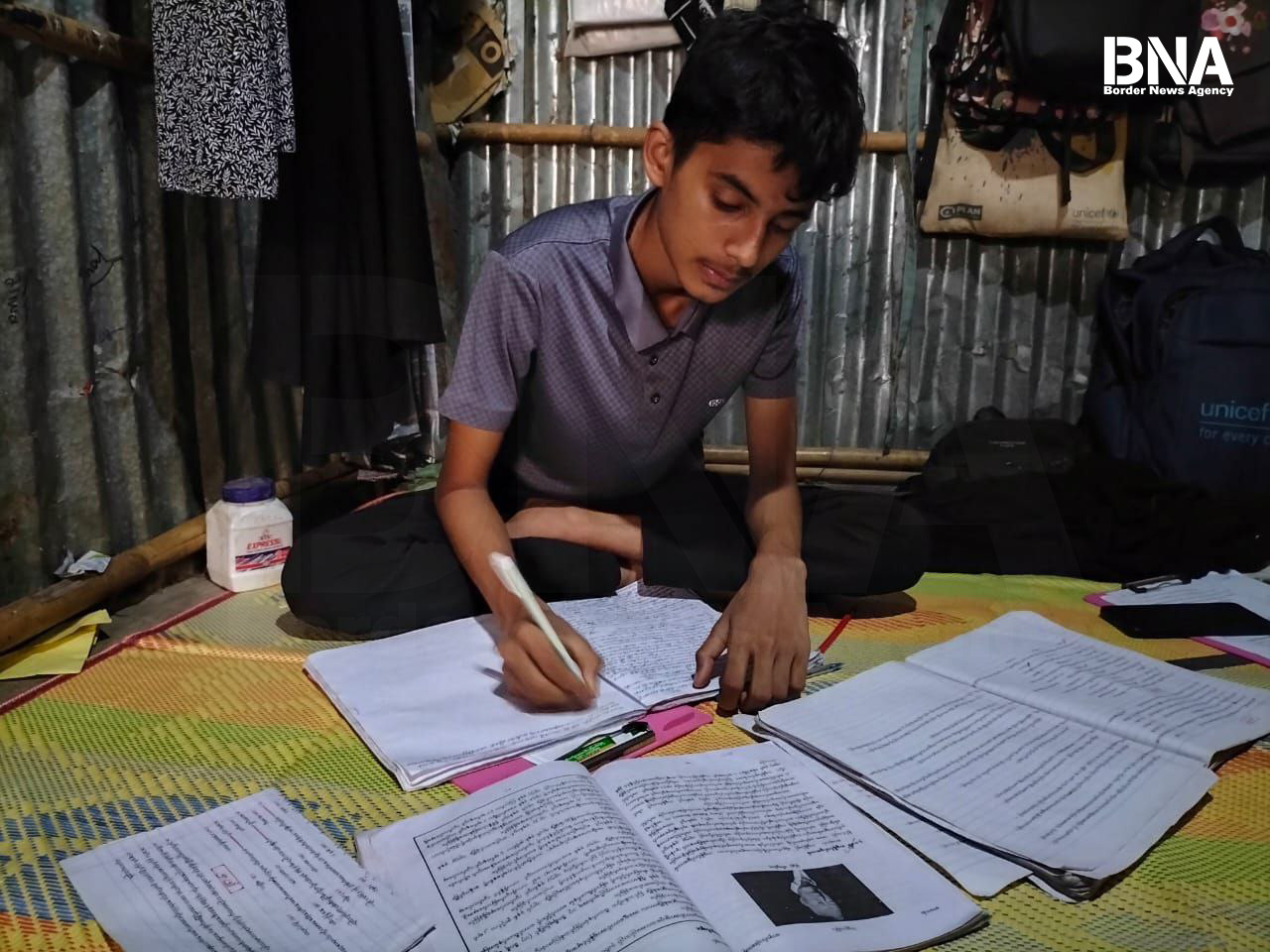

Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh in a quiet corner of his bamboo shelter, 14-year-old Mohammad Faisal sits on the floor, his notebook resting on his lap. The dim glow of a solar-powered lamp flickers as he writes down notes, preparing for his final exams. Despite the challenges of life in the refugee camp, Faisal remains determined to continue his education, hoping that one day, he will achieve his dream of becoming a doctor.

Like Faisal, thousands of Rohingya students are studying hard for their final exams, knowing that education is their only hope for a better future. But for many of them, their academic journey is filled with uncertainty. Before fleeing Myanmar, the Rohingya were systematically denied access to higher education by the Myanmar government. Even now, in the refugee camps, their opportunities for formal education remain limited.

For decades, the Myanmar government imposed severe restrictions on Rohingya students, preventing them from pursuing higher education. In Rakhine State, Rohingya youth were systematically barred from attending universities. Even those who excelled in school found their paths blocked by discriminatory policies.

“In Myanmar, I completed my high school studies, but I was not allowed to enroll in university just because I am Rohingya,” says 18-year-old Sulaiman, who now lives in a refugee camp in Bangladesh. “I watched my Burmese friends continue their education while I was left with no options. It was heartbreaking.”

This systemic discrimination was part of a broader effort to marginalize the Rohingya community. Without access to higher education, generations of Rohingya were denied the opportunity to become doctors, engineers, and professionals trapping them in a cycle of poverty and exclusion.

After fleeing to Bangladesh, Rohingya students hoped for better educational opportunities. However, while humanitarian organizations have established learning centers, the curriculum is limited, and there are no pathways to higher education. The students preparing for their final exams know that even if they succeed, their future remains uncertain.

“I study every day, but I don’t know what will happen after this,” says Ayesha Begum, a 16-year-old who dreams of becoming a teacher. “We don’t have universities. We don’t have certificates that are recognized outside the camps. How will we achieve our dreams?”

Despite these obstacles, Rohingya students remain hopeful. Faisal, the 14-year-old aspiring doctor, refuses to give up. “I study because I believe that one day, things will change,” he says. “Maybe we will be allowed to go back to our homeland and study in real universities. Maybe we will have opportunities to become the people we dream to be.”

Other students share similar ambitions. Some want to become lawyers to fight for Rohingya rights, while others hope to work in journalism to tell their community’s stories. Even without a clear educational pathway, they continue to study, driven by the belief that knowledge is their greatest weapon against injustice.

As final exams approach, the Rohingya students remain committed to their studies, knowing that their fight for education is far from over. Human rights organizations have repeatedly called on the international community to support access to formal education for Rohingya refugees, but progress has been slow.

For now, Faisal and his peers can only hope that one day, they will have the same rights as other students around the world, the right to study, the right to dream, and the right to build a future.

As he closes his notebook for the night, Faisal looks up with quiet determination. “We may not have universities now, but that doesn’t mean we will stop learning. One day, we will prove that Rohingya students can achieve great things.”